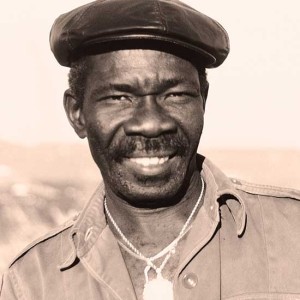

On June 3 1940, a powerful spirit collided with this planet.

One that was to spark, create and develop the weapon of the future, reggae music.

Joseph Benjamin Higgs was born in Kingston and went on to become one of Jamaica’s first music stars and premier songwriters.

Being a very generous soul, he tutored and mentored many of Jamaica’s greatest singers and musicians at his yard in Trench Town including Bob Marley, Jimmy Cliff and Peter Tosh all of whom he ended up touring with.

In 1997 Joe went into the studio in Dublin, Ireland with producer Donal Lunny along with some of Ireland’s top musicians including members of Van Morrison’s band and Hothouse Flowers to create these magical pieces that are now heard for the first time on Joe Higgs – The Godfather of Reggae.

In 1998, the sessions then moved to Grove Studios,Ocho Rios in St. Ann, Jamaica where Joe again worked with Hothouse Flowers and Native Wayne Jobson to add a few more masterpieces to the collection.

Featured on drums on the Jamaican sessions is Max Hinds, son of the great Justin Hinds, another founding father of reggae music.

The sessions were executive produced by Lee Jaffe, producer of two previous Joe Higgs albums as well as albums with Peter Tosh, Morgan Heritage and Barrington Levy.

The tapes were recently discovered and remastered and are being presented as the Godfather of Reggae album for the first time to celebrate Joe’s 75th birthday in June 2015.

These songs are amongst Joe’s best ever and were his final works before his untimely passing on December 18 1999.

That powerful spirit lives on and once again collides with us through this amazing music.

Joe Higgs will forever be one of the true legends of Jamaican music.

To commemorate the release of the long lost Joe Higgs album, The Godfather of Reggae, double Grammy winning producer Native Wayne Jobson shares his memories of his time with the Great One :

“What can I say about a true musical giant and unsung hero, except that I was blessed to have known and learned from him. I first met Joe in 1973 with Bob Marley and we stayed in touch till his passing in 1999. Hanging and playing with him in Trench Town was a true musical mecca for me. His voice was magical, and like a roaring lion could be heard a quarter of a mile away !! His songwriting was impeccable with masterpieces like Stepping Razor (covered by Peter Tosh and Sublime), Life of Contradiction, Lets Us Do Something, Theres a Reward (covered by Slightly Stoopid). My final sessions with him in Jamaica in 1998 were the most special, as he was finally back home (after many years in Los Angeles). With the great Irish band Hothouse Flowers he was able to experiment and create the brilliance heard on the final album The Godfather of Reggae.

Fiachna O Braonáin of Hothouse Flowers wrote these fond memories of his musical brother Joe :

Joe Higgs became a friend for life the minute we met. He became a father, a brother and a teacher all at once as his poetic soul found a home in our hearts where his spirit still resides today.

We first met in a restaurant in the centre of Dublin not long after his plane landed in the summer of 1997. He was wearing green.. a shiny deep green.. rich as the dream he had to mix green with black… Irish music with Jamaican music. It had never really been done before but it made total sense because there we were face to face and side by side from that moment on.

You took the call a little early,

There’s no denying who is king,

We were halfway through the making

Of magic bracelets, magic rings

Magic bracelets, magic rings

“Magic Bracelets” by Hothouse Flowers, written in memory of Joe Higgs.

Hothouse Flowers spent three days in a studio in Temple Bar in Dublin making unforgettable music. Van Morrison dropped in to see what was going on and brought along Haji Akhba and Richie Buckley, his horn players as a gift to the sessions. We were recording And It Stoned Me as it had never been done.. with an Irish-Jamaican pulse running through the veins of the song. Van loved it and Richie and Haji left theoir imprint for us all to hear. We recorded another three songs of Joe’s.. You Don’t Have To See Me, Mistakes That I Made and Vineyard and a friendship was cemented for good.

We came to love Joe as a family member. We spent three weeks together in Ocho Rios, Jamaica in December of 1998 where we celebrated Christmas and rang in the New Year together. Joe had just had the all-clear from cancer surgery and was in great form. The sun was shining and so was he!

We also recorded another seven songs. Each day we got another gem in the can.. and each day we learned more and more about music.. not only jamaican music.. just MUSIC! Joe’s vocal coaching skills came to the fore during the backing vocal sessions where the harmonies that grace the songs were given life. Crucially, Joe also knew when not to coach and just to allow the music to happen.

The following August Hothouse Flowers were touring the United States and when we arrived in Los Angeles, where Joe lived, we called him up to invite him to the gig. It was shocking to hear Joe’s big soulful voice reduced to a small weak sound when he answered the phone.. the sickness had come back and it was not good. We immediately jumped in a car and visited him at home where from his sick bed he dug out the cassette he had of the music we had made in Dublin and in Jamaica. As we listened together one last time his eyes lit up as he quietly declared this had never been done before…. THIS.. was something new. Joe bravely came along to the gig and we hung out afterwards like we always did.. exchanging stories and feeling the love… and he was right. That music hadn’t been done before… But now is has.. it is there for us all.. and Joe Higgs is ever more in our hearts.

Reggae archivist and author Roger Stefens had to say this about his friend Joe :

“One of reggae’s most influential forces, Joe truly lived a life of contradiction – hence the title of his first album. I was privileged to know him for the last 20 years of his life. I found him to be a deep, albeit often contentious thinker, a man who devoted much of his life to the education of others at the expense, perhaps, of his own widely respected career. His road was as bumpity as a Jamaican back country trail, with dashed hopes and a sprinkling of triumphs, enough to earn him the sobriquet of “The Father of Reggae Music” while living mostly in poverty.

We met initially at Jimmy Cliff’s home in Kingston in June of 1976 in the dawning daze of the national state of emergency. Shortly before I had had my pocket picked in Bob Marley’s tiny Tuff Gong shack by one of the music’s biggest stars. Shaken up, Joe and Jimmy assured us that my wife and I were safe with them, which led to several hours of reasoning about Rasta, politricks and the Vietnam War.

During three years of interviews for a now-aborted autobiography, Joe told me of his origins. “I was born on June 3, 1940, same as Curtis Mayfield. My father was a fireman on a ship, he was a triplet, and his mother had 23 sons: three twins and two triplets among 23 kids – all boys! My father was the only one who stayed in Jamaica.”

Joe’s music interest began early, enamored of jazzmen like Billie Eckstein, Louis Jourdan and Louis Armstrong, and blues and r&b masters like John Lee Hooker and Screaming Jay Hawkins. At 16, in the Mico Practicing School for Teachers, the principal, a Mr. Ivan Shaw, ridiculed Joe after he sang in a morning assembly for wanting to enter the National Singing Contest. Two weeks later, Joe won and was once more made to sing in the quad as the principal apologized to him in front of the entire school.

But his world was not genteel. And he was no angel. “I was exposed to all types of crime, and sometimes you’d steal things just to live. From my earliest days I wanted to be someone who would accomplish something in life. When I was a youth I would try hustling too. I knew about shoe making, mixing mortar, carrying stones and cement, common labor work to make some money.”

In the late ‘50s, he said, “A guy named Errol told me he’d like me to teach Bob Marley to sing and play music. He wasn’t doing anything to get anything back, no money changed hands.” And when the nucleus of the Wailers formed, Joe said he was “teaching them to wail. I started to teach them to sing harmony, structuring and all those different things, basic principles of singing. Also how to utilize breath control, which is what we call technique and craft, how to try to preserve as much energy as you can. Soul consciousness. How to use and measure lyrics by virtue of syllables, how to adjust measurement, meter, timing. It took me years to teach Bob Marley what sound consciousness was about. Tosh too. They often couldn’t find the key. For example, on ‘Your Love’ I replaced Peter because he couldn’t sing his part. My baby mother, Sylvia Richards, and I both sang backup on ‘Lonesome Feelings’.”

His 1960 hit “Oh Manny Oh” sold more than 50,000 copies. Producer Coxson Dodd sought him out and became an early champion of his music with his original partner Roy Wilson. But constant dissension over unpaid royalties led Joe to leave Studio One. He returned in a peace gesture with a smash hit called “There’s A Reward for Me.” When he again asked for royalties Coxson sucker-punched him with a pistol, nearly blinding him. Joe spent several weeks in the hospital. Some reward. He bled from his eyes and suffered years of debilitating headaches afterwards.

Savvy to the business side of things, Joe was one of the first artists to retain control of his own masters, and ask for contracts to be signed. This limited his output but resulted in a career where nearly every single song truly counted. Because he shared his legal knowledge with fellow singers he was rapidly shunned by the power mongers of Jamaica’s brutal music world. “I was banned from the business in the mid-‘60s,” he said ruefully. “ Byron Lee kept me out for a while. It was the same time that the Jamaican government was choosing artists to represent the country at the New York World’s Fair in 1964.” It was the time of the undisputed reign of Jamaica’s greatest instrumental lineup ever, the Skatalites, led by Don Drummond at the height of the ska craze. Joe was still angry thirty years later at the thought. “So instead of me and the Skatalites and the other creators, they send up Byron Lee. They claimed we were ganja smokers and couldn’t be trusted.”

Some measure of revenge came in 1972 when he won the Festival Song Competition with “Invitation to Jamaica,” which caught the attention of Chris Blackwell of Island Records. Joe recalled, “Chris gave me $500 a month to take care of my expenses. The strategy was to keep me on hold so they can promote Marley. When I completed ‘Life of Contradiction’ for him, Chris wouldn’t take it for distribution, claiming I was very very far out in front of those other guys, they don’t know where to place me.”

It has often been said of Joe that he was ahead of time, which stifled him in terms of popular acceptance. He was aware of the criticism. “I like phrasing my voice like an instrument. I love jazz. People will always be ahead of people. Some walk, some run, some creep. I’m not concerned about success. Music is my teacher. But it’s not good to be ahead of time, because life is a progression.”

Joe’s international reputation has always rested in large part as the man who taught Bob Marley to sing. But their relationship was fragile. Bob generated tens of millions of dollars during his short international career. Joe saw virtually no trickle-down. “Marley was a user in a lot of ways. For example – here is a man who had a tour pending in the fall of 1973, his first U.S. tour, and at the very last minute, maybe a week before leaving, Bunny Wailer walked away for whatever reason. With that short a time, Bob came to me on his knees and asked me to join them as the ‘most fitting replacement’ for Bunny: I can play drum, I can sing harmony. He got us to go on the road voluntarily, I wasn’t offered a salary or anything. I wasn’t paid. I was not being thanked, no compensation at all.

“When my brother died in ’74. we had no money to bury him. I decided to play the role of a madman. I went to Bob’s at Hope Road and I stood up and wasn’t saying anything. He looked at me, ‘Wha’ppen, Joe,’ called me by name. I never respond. Bob said, ‘Well, them finally fuck up Joe now. Joe is mad now!’ Offer me spliff, banana, I never respond to anything so he would think i was really out there in space. However, I waited fe a while, an hour or so. Then I said, ‘Can I talk to you a moment?’ Him say, ‘Yes man,’ and took me upstairs. I said ’You don’t really owe me any money because I never really sign a contract with you, but I told you as a member of the Wailers I never got nothing from you.” Bob said, ‘How much i owe you?’ I said, ‘Just give me something,’ and Bob said, ‘I’ll give you $2,000 JA.’ When I got the check it was for $1,500. First money I got from that tour. I used some of that to bury my brother.”

He went on a U.S. tour in ’75-76 as Jimmy Cliff’s bandleader and reliever for a couple of songs in the middle of Jimmy’s set. A reviewer of their New York City show ecstatically pointed out songs in which “Jimmy” really blew the audience away. Turned out they were Joe’s numbers, and he was dropped from the tour.

“When I did ‘Ah So It Go,’ [when you no have big friend] Michael Manley was using this song and ‘a little bird’ came to me and told me that they wanted to kill me because I embarrassed the Prime Minister, this was in1980. At the time, I was at Garveymeade in St. Catherine, and there were times I would be six months behind with my mortgage. Because people thought I was in the political arena with this song, my house was auctioned. I lost my house. Jimmy, Bunny, Rita, Bob – I went to all them and asked them for assistance. I said I would work in return, or do something to repay them. My house was sold over my head.” They gave him nothing.

“Respect? Never got it.”

Although he maintained tight control of all his copyrights, others such as Harry J and Blackwell both claimed ownership of his songs at various times. “Stepping Razor,” Joe’s incendiary Festival Song entry, was co-opted by Peter Tosh who placed his name on it. Eventually, through the aid of a sympathetic Jamaican government official, Joe received a first payment of $17,000 in back royalties and the acknowledged title of composer.

In ’79 Joe released his second album, “Unity is Power.” Its cuts included love songs and an herbal observation, plus the standout title track and “Sons of Garvey,” originally recorded as a duet with Jimmy Cliff on his Sunpower label. An all-star lineup joined him in March of 1978 at the Aquarius Studio in Kingston for his self-produced sessions, including Santa Davis on drums, Bagga Walker and Boris Gardner on bass, Cat Coore on guitar, Keith Sterling on all the keyboards, Cedric ‘Im Brooks on tenor sax and Joe himself on congos.

The following year, Bob threw Joe some crumbs by bringing him into the Tuff Gong studio to sing backup on “Coming in from the Cold.” “It was three weeks before Bob paid me, $300! Those were times when I really needed the money. He got where he was because of me, and he’s making his money because of me, but he’s keeping me waiting for the money.”

Discouraged, at the dawn of the ‘80s Joe arrived in L.A. He moved here permanently by 1984, becoming a guiding force for the growing numbers of fledgling local reggae bands. He was backed over the years by several different aggregates, all of whom testified to the minute control exercised by Joe in meticulous rehearsals. He did for them what they knew he had done for Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer, the Wailing Souls and countless others – and they were humbled by that knowledge.

Joe often told his apprentices about the greats, Sam Cooke and Otis Redding. “They both recorded ‘Try A Little Tenderness’,” he explained. “Sam’s was sweet, sooo sweet, but Otis’s version was pure soul.” Using his voice like a trumpet, Joe ennobled the slightest lyric and made it the stuff of epic verse. His stage patter could easily run from Yeats to Shakespeare. He was intolerant of ignorance and yearned to make everyone strive to be a better person.

Joe could be disputatious about many things that most others had already decided were correct. Take, for example, the arrangement of color on Rasta flags of red, gold and green. Traditionally, green has been on top. But, no, said Joe. “How could that be? Red is for the sun, and the green is the grass of the earth. How could green be in the sky?”

On Jamaica’s national motto, “Out of Many We Are One,” which recalls all the different races and nationalities that make up the Jamaican people, Joe chose to radically differ. “What that really means,” he proclaimed adamantly on many occasions, “is that they went to all the countries of the world and found the one black man there and brought him to Jamaica.”

Joe made a distinct connection between faith and fate. “Fate,” he said, “is the outcome of faith. It is saying, your fate is your destiny. To me I was destined to be a messenger of music. That’s my faith. The destiny is the realization, it’s not the end, but it is in accordance with the word fate. I think that being human means limitation, therefore the fate is unknown, because it is in the category of the future, which is also unknown. I know what my faith is, in that I always believed that by my music I would be prosperous and successful and be meaningful and of assistance to others.

“No matter what I have done for these great monsters of reggae music, it is not that they did anything for me in return, but it is because of them most of the time why I’m remembered. And why? Because I have contributed somewhere along the line in their upcoming, and these things to me are the facts I’m trying to say, that are seeds planted by a spiritual farmer. These earthly experiences are rewarded to me by the spiritual power of God. Therefore, because I gave first, like how God gave His love, His son, to us, my faith set me free toward that fate.”

Joe grew deeply depressed about the direction the music took in the aftermath of Marley’s passing in May of 1981. The biggest star to emerge was the salacious foul-mouthed rapper, Yellowman. Joe was unequivocal in his prophecy, commenting on “King” Yellowman’s performance at a December festival in Montego Bay in 1981. “The music festival was all right except for Yellowman, who was very out of order and it makes me wonder if governments are going to allow this man to destroy the morals of the future generation with slackness before dignitaries and children.“

Having given Bob Marley the essential ingredients for a professional career, Joe Higgs was approached to do the same for Bob’s children in the mid-‘80s as they embarked on their own musical excursion as Ziggy Marley and the Melody Makers. Joe recalled ruefully that “In that time, their manager was a man named Dennis Wright . He called me to a meeting up at Tuff Gong, and he told me that Rita Marley wanted me to give some vocal lessons to the Melody Makers and the I Three. First they asked me what is my fee, and I had no figure, I never before teach anyone for pay. I had no idea. They said they were going to do a research to see what the general music instructors were getting. Dennis Wright told me that the most expensive instructor at the time was getting JA $15 an hour. But they said they would offer me $25 an hour. Okay. So the first engagement I was given with them was a Saturday morning at the studio at 56 Hope Road. And the first lesson that I gave them toward structure. harmony and those things was two songs, and they walked from me into the studio and started voicing. So I said to myself, damn, these guys are going to have me produce four songs for a hundred dollars. So I said to Dennis, you can have me for the producer of this whole project for JA $25 an hour, and I could end up prod. the entire project for under $500 – more like ten songs for $25 is $250. And when I draw that to his conscience, he therefore said to me, ‘Okay, we’re going to give you $100 an hour.’ I said, ‘Forget it.’ And I walked away. That was the end of me and the Melody Makers and the rest of the possibilities of working with that organization.”

He turned not long after to Lenny Kravitz, a self-described huge fan of Joe’s work. They worked on an album, composing songs together, but the project eventually fell through, another dashed dream.

In the late ‘90s, toward the end of his life, he journeyed to Ireland where Hothouse Flowers laid eleven tracks with him. Van Morrison visited the Dublin sessions and offered his horn section, who were sitting outside in a car, for Joe’s use. The respect shown to Joe in those sad final years did not make up for the lack of financial sustenance. As he lay dying and penniless in a welfare hospice in Los Angeles at the end of 1999, his daughter Marcia put out a call to disc jockeys to play “Unity is Power” and share a prayer with listeners.

It is unnervingly ironic that the last record released under Joe’s name came just two months before he passed. It was a reissue from Coxson Dodd of Joe’s “Worry No More.” On the flip side he placed, not a dub as would have been usual, but a vocal by a different artist, Derrick Morgan. It was called “Leave Earth.”

I was asked to do the eulogy at his funeral, held in a black church on Adams Boulevard. Many of his dozen children and dozen grandchildren attended. Joining them in the congregation that night, we all sat imagining the Reward awaiting there for Joe in Zion”.

Joe died of cancer on 18 December 1999 at Kaiser Hospital in Los Angeles.

At the time of his death he had been working on a collaboration with Irish artists, including John Alexander Reed and Ronald Padget for the Green on Black album which became part of the Godfather of Reggae album. He is survived by twelve children, including his daughter Marcia, who is a rapper, and son Peter, a studio guitarist.

Long Live Joe Higgs !!